The Sacrament of Holy Eucharist

The chalice of benediction, which we bless, is it not the communion of

the blood of Christ? And the bread, which we break, is it not the

partaking of the body of the Lord ?

1 Corinthians 10, 16

The Holy Eucharist is a central aspect of Catholic faith, representing the body and blood of Christ that are present in the consecrated host on the altar. Catholics hold that the bread and wine transformed during the Eucharist become not just symbols, but the actual body, blood, soul, and divinity of Jesus Christ. This belief underscores the significance of the Eucharist, elevating it above other sacraments as it is seen as “the perfection of the spiritual life and the end to which all the sacraments tend.” According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, particularly in paragraph 1374, the Blessed Sacrament contains “the body and blood, together with the soul and divinity, of our Lord Jesus Christ,” meaning that the entirety of Christ is truly, really, and substantially present in the Eucharist. This substantial presence is what differentiates the Eucharist from mere symbols, highlighting that Christ, in his divine human form, is wholly and entirely present during this sacred celebration.

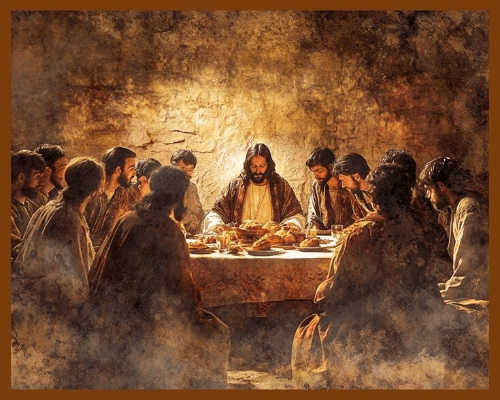

The Eucharistic sacrifice of Christ’s body and blood was instituted at the Last Supper to maintain the remembrance of His sacrifice on the cross throughout time, until his eventual return in glory. This sacrament serves as a memorial of His death and resurrection, entrusted to His Church by Christ. The Blessed Sacrament is essential to Christian initiation, as outlined in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC, 1322). Through Baptism, individuals are elevated to the dignity of the royal priesthood, allowing them to participate in the Lord’s sacrifice through the Eucharist.

Moreover, the Holy Eucharist is described as a sacrament of love—a symbol of unity, a bond of charity, and a Paschal banquet. In this sacrament, Christ is consumed, grace fills the mind, and a promise of future glory is offered (CCC, 1323). The Eucharist acts as an effective sign and a vital cause of communion in divine life and the unity of the People of God, which is fundamental for the Church’s existence (CCC, 1325). God’s sanctifying action reaches its peak in the Eucharist; the celebration of this sacrament during Holy Mass represents the sacrifice of Christ on the cross and facilitates the dispensation of sanctifying grace to the faithful.

In the Old Covenant, bread and wine were offered as sacrifices, representing the first fruits of the earth, and symbolizing a gesture of gratitude toward the Creator. This practice remains a significant component of the Jewish Passover meal. During Passover, the Israelites consume unleavened bread to commemorate their swift escape from Egypt after gaining their freedom. This tradition serves as a reminder of the manna provided in the desert during the Exodus, encouraging them to live according to God’s word and emphasizing His unwavering faithfulness to His promises. At the conclusion of the Passover meal, the Cup of Blessing contributes to the celebratory nature of the wine while also incorporating an eschatological aspect, reflecting the messianic hope for the restoration of Jerusalem. When Jesus established the Eucharist, he provided a new and definitive interpretation of the blessings associated with the bread and the cup of wine.

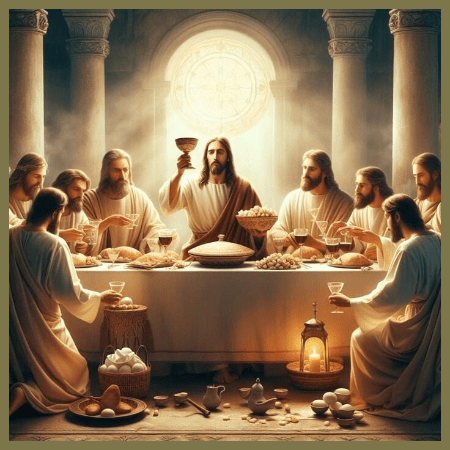

The traditional Passover meal consists of four distinct phases, each involving the serving of a cup of wine, totaling four cups in all. The first cup, known as Kiddush, is mixed with water and is consumed during the introductory rite. In this phase, the family’s father leads a prayer of thanksgiving and offers a blessing for the food, while the appetizers are enjoyed. During the second phase, a second cup of wine, referred to as the Haggadah, is mixed with water but not consumed. Instead, this segment features a dialogue in which the son asks his father questions about the original Passover night and the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt. In response, the father cites passages from the Pentateuch in the Old Testament, providing context and teachings related to these events.

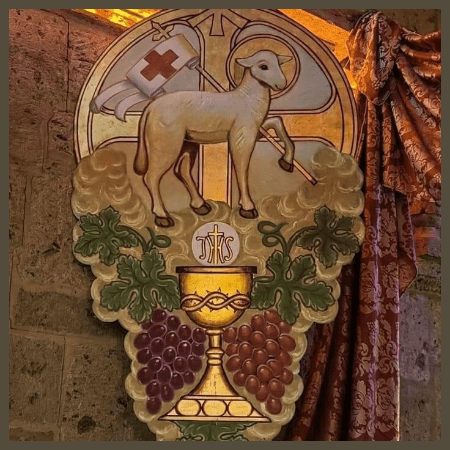

In the Gospels, Jesus is depicted as partaking in a ritual following the consumption of the first and second cups of wine during Passover. He continues by mixing and serving the third cup, known as the Cup of Salvation or Cup of Blessing (Berekah), which is typically served during the main meal course that includes unleavened bread and the flesh of the sacrificed Passover lamb. This moment is significant as Jesus blesses and thanks God for providing bread and the fruit of the vine, as described in Luke 22:14-20. In this context, Jesus is seen as identifying himself with both “the bread of life” and the paschal lamb. He is referred to as the Lamb of God, whose purpose is to take away the sins of the world through the outpouring of his blood, which symbolizes the new wine of salvation that the prophets had foretold. This connection is supported by various prophetic texts, including Amos 9:11, 13; Joel 3:1; and Isaiah 24:7, 9, 11; 25:6-8, as well as the account in John 2:1-11.

In the context of the Last Supper, Jesus established a renewed paschal sacrificial meal using bread and wine that emphasizes a future-oriented perspective rather than merely remembering the past. This meal signifies Jesus taking the place of the Passover lamb, foreseeing his impending sacrifice for the forgiveness of sins on the Cross. His self-sacrifice commenced at the Last Supper, which served as a precursor to the events of Calvary. During this meal, Jesus blessed the bread and wine, transforming them into his own body and blood for the apostles to consume, thus substituting the traditional elements of the Passover meal. In the Jewish Passover tradition, it is essential for the flesh of the sacrificed lamb to be eaten, along with the sprinkling of its blood; otherwise, the sacrifice does not fulfill its intended purpose (Ex 12:5-8; 24:8; cf. Jn 6:54).

The Last Supper, which Jesus celebrated with his apostles during the Passover meal, establishes a profound significance for the Jewish Passover. This event symbolizes Jesus’ transition to his Father through his death and resurrection, which is referred to as the new Passover. The Lord’s Supper serves as both a fulfillment of the Jewish Passover and a foreshadowing of the final Passover of the Church in the glory of the kingdom, as noted in the Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC, 1340). Central to the Eucharistic celebration are the bread and wine that, through Christ’s words and the invocation of the Holy Spirit, become His Body and Blood. In adherence to the Lord’s command, the Church continues to practice this ritual in remembrance of Him and in anticipation of His glorious return, echoing His actions during the eve of His Passion: “He took bread… He took the cup filled with wine…”

The Church interprets the actions of the king-priest Melchizedek, who offered bread and wine, as a foreshadowing of its own sacrificial offering, as noted in Genesis 14:18. By celebrating the memorial of Christ’s sacrifice, the Church follows the command of the Lord, presenting to God the offerings He has provided: the gifts of creation—bread and wine. Through the power of the Holy Spirit and the words of Christ, these elements are transformed into the body and blood of Christ, which serve as a means of forgiveness for sins.

In this sacrificial offering, Christ is believed to be genuinely and mysteriously present under the appearances of bread and wine. The faithful hold a sacred belief that the Holy Eucharist functions as a sacrifice of praise and thanksgiving, serving as a memorial of Christ’s body and blood. This real presence of Christ is realized through the invocation of His word and the power of the Holy Spirit. Consequently, our Lord is substantially present in the Eucharist, akin to His presence with His Most Blessed Mother Mary and His beloved disciple at the foot of the cross.

The Eucharist is defined as a “sacrifice of thanksgiving to the Father,” serving as a means for the Church to express gratitude to God for His numerous blessings, including those received through creation, redemption, and sanctification (CCC, 1360). The term “Eucharist” is derived from the Greek word “eucharistia” (ευχαριστία), which primarily translates to “thanksgiving.” Furthermore, the Eucharist acts as a “sacrifice of praise,” allowing the Church to glorify God on behalf of all creation. This act of praise is made possible solely through Christ, who brings believers together in unity with Himself, facilitating their shared worship and intercession. As a result, the sacrifice of praise is presented to the Father through Christ and with Him, ensuring that it is accepted in His name (CCC, 1361).

The Eucharist is a profound and central aspect of Christian worship, described as “the memorial of Christ’s Passover.” This sacrament involves not only a remembrance of Christ’s Last Supper and His sacrificial death on the cross but also signifies the making present of that unique sacrifice during the liturgy of the Church, which is recognized as the Body of Christ. Within each of the Eucharistic Prayers, there is a pivotal moment after the words of institution where a prayer known as the anamnesis, or memorial, is offered. This prayer serves to commemorate and make present the mystery of salvation through Christ’s sacrifice (CCC, 1362). Consequently, the sacrifice of the Mass is regarded as the highest form of worship that believers can offer to God, integral to the Catholic faith. This concept parallels the sacrifices that the ancient Israelites made in the context of the Old Covenant, which served as a means of atonement and thanksgiving. The Mass encapsulates the fulfillment of these sacrifices by embodying the ultimate sacrifice of Christ, drawing believers into an intimate connection with the grace and mercy of God.

The Eucharist is also a sacrifice, as it is the memorial of Christ’s Passover, which holds profound significance in the context of the Eucharist, embodying the sacrificial nature inherent in our Lord’s words during the Last Supper. In the Gospel of Luke, Jesus declares, “This is my body which is given for you” (Lk 22:19) and “This cup which is poured out for you is the New Covenant in my blood” (Lk 22:20). These statements highlight the sacrificial offering of Christ’s body and blood, illustrating that in the Eucharist, He provides us with the very body He sacrificed on the cross, along with the blood that He “poured out for many for the forgiveness of sins” (Mt 26:28).

Just as the traditional Passover meal serves as a remembrance of the Israelites’ deliverance from slavery in Egypt, the Lord’s Supper functions as a memorial meal that signifies the ultimate sacrifice of Jesus. By recalling past events, the Eucharist actively brings that moment into the present, creating a profound connection for the faithful. Thus, the Eucharist is not merely a ritual; it is a sacrificial meal that sacramentally re-presents the singular sacrifice of the cross to us. It is essential to understand that the Eucharist serves as a living memorial, making present the one, eternal sacrifice of Christ. This act of remembrance enables the grace and salvific fruit of that sacrifice to be applied to the lives of the faithful in the present, underscoring the transformative power of the Eucharist throughout the Church’s history.

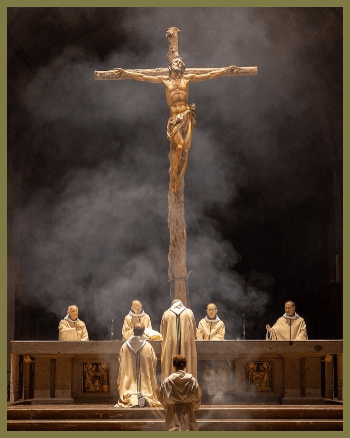

Jesus, recognized as Lord and Savior, dedicated Himself to God the Father through His death on the cross, which is viewed as the ultimate act of our eternal redemption. His priesthood, instituted during the Last Supper, was intended to transcend his death, leading him to establish a visible sacrifice for his Church. This sacrifice, accomplished once and for all on the cross, is meant to be represented and commemorated throughout history, until the end of time. The Eucharistic sacrifice serves as a means of applying the redemptive power of the cross, providing a way to forgive the sins we commit daily, as highlighted in scriptures such as 1 Corinthians 11:23 and Hebrews 7:24, 27.

The sacrifice of Christ on the cross and the Holy Eucharist are understood as a single, unique sacrifice that was completed once and for all. The effects of this sacrifice are applied continuously throughout time, up to the end of the world. During each celebration of the Mass, the sacrifice of our Lord on the cross is made present, emphasizing that this act is not repeated. Rather, Christ’s sacrifice is singular and everlasting, transcending time and space even though the Eucharist is celebrated regularly. The one sacrifice on the cross was made present at the Last Supper, just as it is in every daily Mass, highlighting the continuity of this central event in Christian faith.

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is established during the consecration, known as the epiclesis, which occurs by the power of the Holy Spirit. This presence continues as long as the Eucharistic species remain. In the Eucharist, Christ is fully and wholly present in each species—both in the bread and the wine—and remains entire in each of their parts. This means that the act of breaking the bread does not divide Christ (CCC, 1377). Because Christ is truly and substantially present in the Eucharist, Catholics show adoration and worship towards it. It’s important to note that this worship is not directed at the accidental properties of the bread and wine that are perceivable through the senses. Instead, it is the crucified Christ, present in the Eucharist, who is honored and adored, encompassing his body, blood, soul, and divinity. Historically, the Blessed Virgin Mary and the disciple John were among the first to offer this profound adoration to our crucified Lord at Calvary.

In the Catholic tradition, the Eucharist is a central element of worship during the sacred liturgy of the Mass, signifying the belief in the real presence of Christ in the forms of bread and wine. This reverence is often demonstrated through physical acts such as genuflection or deep bowing. The Catholic Church also practices a form of adoration known as a cult of adoration, where the Blessed Sacrament is honored through periods of silent reflection at specific times of the day, typically before the tabernacle located behind the altar where the sacred Host is stored. Additionally, solemn veneration is expressed when the consecrated host is displayed in a monstrance on the altar or during processions.

The altar serves as a central element in the Church’s celebration of the Eucharist, symbolizing two interconnected aspects of the same sacred mystery: it represents both the altar of sacrifice and the Lord’s table. The Christian altar is emblematic of Christ Himself, who is present among the faithful not only as the victim offered for reconciliation but also as the heavenly food that nourishes believers. The Catechism of the Catholic Church (CCC, 1388) emphasizes this significance. Additionally, in the Gospel of John, Jesus extends a compelling invitation: “Truly, I say to you, unless you eat the flesh of the Son of Man and drink his blood, you have no life in you” (Jn 6:53), highlighting the importance of receiving Him in the sacrament of the Eucharist.

The concept of the Holy Eucharist is referenced throughout both the Old and New Testaments. The earliest mention can be found in the Book of Genesis 14:18, where the term “priest” is introduced. In this context, the priest is Melchizedek, who serves a dual role as both a priest and the king of Salem, a city later identified as Jerusalem (as noted in Psalm 76:2). Melchizedek’s significance lies in his offering of bread and wine as a sacrifice to God. This act serves as a foreshadowing of Christ’s own royal priesthood. Unlike the Levitical priesthood, Christ’s priesthood is established in the order of Melchizedek, as articulated in Hebrews 5:5-6. In this way, Jesus represents the King of His Father’s heavenly kingdom on earth, which is symbolically understood as the New Jerusalem, or the Church, coming down from heaven.

The Old Covenant Levitical priesthood was designed by God to serve a temporary role, as indicated in Hebrews 7:11-12 and 9:10. This system was established to transition to a new order. A key figure in this transition is Melchizedek, who appears in the biblical narrative long before the Levites emerged—specifically, he existed many decades prior to the birth of Levi, Abraham’s great-grandson, and over three hundred years before the Israelites received the Mosaic law in Exodus 20. The existence of Melchizedek’s priestly order prior to the law implies that it was not limited by the Levitical regulations concerning the priesthood. Consequently, this allowed Jesus, who was from the tribe of Judah, to fulfill the role of High Priest before God in his sacred humanity after his resurrection and ascension to heaven.

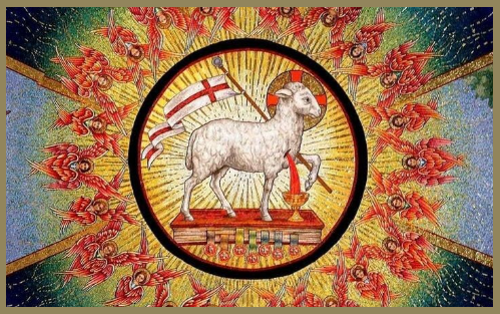

In Hebrews 9:23, it is noted that the sacrifices of the Old Covenant serve as representations or copies of the heavenly realities. In contrast, a superior sacrifice is presented to God daily in heaven, which was revealed to John in his vision. Although Jesus’s crucifixion was a singular event in history, the text refers to this heavenly sacrifice in Hebrews as “sacrifices.” This terminology reflects the idea that while the crucifixion occurred once, its impact is timeless and is re-presented sacramentally through the celebrations of Holy Mass. Furthermore, biblical prophecy suggests that God’s earthly kingdom, embodied by the Church, comprises a sacrificial priesthood that is intended to endure perpetually. This promise is fulfilled through the priests of the Catholic Church, who offer the sacrifice of Christ in every Mass celebrated globally, ensuring that it continues “from the rising of the sun to its setting” until Christ’s return in glory, as noted in Jeremiah 33:18.

The phrase “sacrifice of praise” found in Hebrews 13:15 refers to the toda offering made by Christ in the heavenly sanctuary, which is distinct from those made by human hands. Like the Old Covenant’s toda offerings, this sacrifice must be consumed to be of benefit, as indicated in Leviticus 7:12-15 and 22:29-30. In the context of the Eucharist, the Mass represents a newly defined sacrifice characterized by “praise and thanksgiving.”

The Eucharistic sacrifice alluded to in Hebrews 9:23 fulfills the prophecies of both Jeremiah and Zechariah. Zechariah’s prophecy (9:15) states that the sons of Zion will drink blood like wine and be saved, emphasizing the significance of partaking in the body and blood of Jesus for spiritual life. Believers approach Jesus as the mediator or High Priest of a new covenant, aligning with Hebrews 12:23-24, which speaks of the sprinkled blood that offers a better message than that of Abel. This understanding suggests that the offering of our Lord’s sprinkled blood is ongoing. It is made sacramentally present to the faithful through priests of the New Covenant, who act in the person of Christ. These priests trace their authority back to Christ as the High Priest in the order of Melchizedek, as pointed to in 2 Chronicles 26:18.

The connections between the Old Testament and the Eucharistic sacrifice are significant and prophetic. Psalm 110:4 highlights that Jesus is designated as the eternal High Priest and King, akin to Melchizedek, the biblical king-priest. This suggests the existence of an everlasting sacrifice involving bread and wine, which is ultimately realized in the Eucharistic sacrifice of the Mass celebrated by the Catholic Church. Additionally, the prophet Malachi (1:11) reinforces the idea that this sacrifice will be offered universally throughout the world, emphasizing its timeless and transcendent nature that brings salvation.

Moreover, the Feast of Unleavened Bread, celebrated during Passover, is established as a lasting ordinance (Ex 12:14, 17, 24; cf. 24:8). This ordinance finds its ultimate fulfillment during the Last Supper. The concept of the marriage feast of the Lamb, representing the Bread of Life, signifies the eternal celebration in heaven, which spans from these earthly observances. The memorial celebration of the Lord’s Supper, or the Paschal feast, conducted during Mass, serves as a sign of this heavenly banquet and is an integral part of the divine feast awaiting believers.

The Old Testament contains elements that foreshadow the necessity of consuming Christ’s sacrifice. In the Old Covenant, priests performed atonement for sins through a guilt offering that involved an unblemished lamb, which had to be consumed for the offering to be effective (Lev 19:22). Jesus fulfills the roles of both our eternal High Priest and the sacrificial Lamb of God, sent to take away the sins of the world. His singular act of atonement must also be consumed to be of benefit to our souls.

The paschal lamb, as outlined in Mosaic law, had to be both unblemished and eaten (Ex 12:5; Isa 53:7). Jesus is recognized as the unblemished Lamb of God, having been conceived and born without sin, and He likewise must be consumed in the New Dispensation (Lk 23:4, 14; Jn 18:38). Moreover, during the first Passover, blood from a sacrificial lamb was to be sprinkled on the doorposts of the homes of the Israelites to protect their firstborn sons from death. In the Eucharistic sacrifice referenced in the Letter to the Hebrews, this act parallels the sprinkling of Christ’s blood, which offers believers protection from the eternal death of the soul.

In the biblical narrative, God provided His chosen people with manna, a form of bread from heaven, to sustain them during their journey to the promised land. This event serves as a precursor to the spiritual nourishment offered through the true bread that has come down from heaven, which is essential for sustaining believers on their journey to eternal life in heaven (referenced in Exodus 16:4-36, Nehemiah 9:15, and John 6:32-33).

The Old Covenant was marked by a significant meal shared in God’s presence (Ex 24:9-11). At the same time, the New Covenant is fulfilled through the Eucharistic supper, where the body and blood of Christ are presented under the forms of bread and wine (Mt 26:26-29, Mk 14:23-24, Lk 22:20). Scripture suggests that those who partake of this spiritual food will develop a deeper hunger and thirst for it (Sirach 24:21). Jesus emphasizes this importance by stating, “He who eats my flesh and drinks my blood has eternal life, and I will raise him up on the last day” (Jn 6:54), underscoring the vital significance of the Eucharist in the life of believers.

In the New Testament, there is a significant emphasis on Jesus’ promise of his real presence in the Holy Eucharist. This promise is made during his time in Capernaum, specifically on the eve of Passover, when lambs are gathered and prepared for consumption (Jn 6:4). Throughout his discourse, Jesus makes a noteworthy declaration by stating four times, “I am the bread from heaven” (Jn 6:35, 41, 48, 51). The repetition of this phrase suggests that he intends for his message to be understood literally rather than metaphorically.

Further, Jesus draws a parallel between himself and the manna that descended from heaven during the Exodus, which the Israelites consumed to sustain their physical lives. However, he clarifies that the bread he provides offers sustenance for eternal life with God (Jn 6:27, 31, 48-49). He further elaborates that the bread he gives is his flesh, intended for the life of the world (Jn 6:51).

In this context, Jesus aligns himself with the paschal lambs, which are sacrificed during Passover as an atonement for sin and must be consumed to fulfill their purpose. As the Lamb of God, Jesus offers his flesh to be eaten in the Eucharist, which is presented under the appearance of bread. This act is part of the sacrificial offering made by our High Priest in the order of Melchizedek, reinforcing the importance of the Eucharist in Christian belief.

At this point in our Lord’s Eucharistic discourse, the Jewish listeners are both shocked and offended by his words because they interpret him in a strictly literal sense (Jn 6:52). Their confusion leads them to question one another, asking, “How can this man give us his flesh to eat?” Rather than clarifying their misunderstanding, Jesus intentionally refrains from correcting their literal interpretation of the text. This is significant, as they have correctly interpreted his words within their own context. In fact, he amplifies his teaching by emphatically asserting the necessity of consuming his flesh, swearing an oath to emphasize this reality. He states explicitly four times that they must eat his flesh and drink his blood (Jn 6:53-58).

Through this insistence, our Lord drives home an essential theological truth regarding the Eucharist, foreshadowing his sacrificial death and the significance of the elements of bread and wine. He is not merely speaking metaphorically; he is preparing them for the profound mystery of the Eucharistic sacrifice that would soon be realized. For Catholics, this teaching has been a cornerstone of faith since the time of the Apostles, affirming that Jesus truly offers His body and blood in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, which is manifested under the appearances of bread and wine. This belief stems from a profound understanding of the sacramental presence that permeates the teachings of the early Church and continues to shape Catholic worship and theology to this day.

The event of Christ presenting Himself as the Passover lamb during the Last Supper marks a significant transformation for New Covenant believers, establishing the celebration of the Eucharist. On the night of the Jewish Passover, Jesus reinterpreted the traditional Passover meal, which usually included a sacrificial lamb. To grasp the implications of this change, it is essential to examine the details of the Lord’s Supper more closely. Jesus led the Passover Seder with His apostles, a ritual that involved drinking four cups of wine. Notably, He is recorded as serving only the third cup, known as Berekah or the “Cup of Salvation” (as referenced in Matthew 26:29 and Mark 14:25). The Apostle Paul later refers to this “Cup of Blessing” in relation to the Eucharist, thereby linking the Seder meal to the Eucharistic sacrifice (1 Corinthians 10:16). This third cup symbolizes the Paschal sacrifice of Christ, who is recognized as the Lamb slain for the sins of humanity.

In the Last Supper, Jesus notably does not serve the fourth cup, known as the Hallel or “Cup of Consummation.” This omission is significant as it connects the Eucharistic sacrifice associated with the Seder meal to Christ’s ultimate sacrifice on the Cross. Essentially, both events represent one unified sacrifice. According to Dr. Brant Pitre, the Last Supper serves as a foreshadowing of Jesus’ sacrificial death. This connection is further highlighted when Jesus finally consumes the fourth cup just before his death on the cross, culminating in his declaration, “It is consummated” (Jn19:29-30; Mt 27:48; Mk 15:36).

The tradition of using sour wine on a “hyssop” branch can be traced back to the first Passover, where it served as a means to sprinkle the blood of the lamb on the doorposts, as described in Exodus 12:22. Priests also observed this practice during sacrificial offerings under the Old Covenant. This connection links the sacrifice of Christ to the lambs that were slaughtered and consumed during the Passover Seder meal, which concluded with the drinking of wine from the Cup of Consummation. Therefore, the significance of Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross is rooted in events that began in the upper room and reached completion at Golgotha (Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist, Doubleday, 2011).

The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass serves as a re-presentation of this singular sacrifice. The New Covenant’s Lord’s Supper, or Seder meal, makes Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross perpetually present, symbolizing the heavenly marriage feast. St. Paul emphasizes the importance of celebrating the Eucharistic feast in 1 Corinthians 5:8, underlining the necessity for believers to partake in the flesh of the Lamb of God and to drink His blood in the Blessed Sacrament to attain holy communion with God.

Hence, the Lord’s Supper is more than just a symbolic memorial meal; it serves as a marriage feast that signifies the establishment of the New Covenant. Within this framework, the Eucharist presents Christ’s one eternal sacrifice in a tangible way. Author John Salza (The Biblical Basis of the Eucharist: Our Sunday Visitor, 2008) highlights that Scripture supports this understanding through the words of consecration—“Do this in remembrance of me” (touto poieite tan eman anamnasin) spoken by Jesus during the Last Supper (Lk 22:19; 1 Cor 11:24-25). This phrase can be interpreted as an instruction to “offer this as a memorial sacrifice.” The Greek verb poiein (ποιεῖν), translated as “do,” is specifically used in the context of offering a sacrifice. For instance, in the Septuagint, the term poieseis (ποιέω) is employed in relation to the sacrificial lambs presented on the altar (Ex 29:38-39). Additionally, the noun anamnesis (ἀνάμνησις), meaning “remembrance,” connotes a sacrifice that is made present in real-time through the power of God in the Holy Spirit, serving as a reminder of the actual historical event (Heb 10:3; Num 10:10).

The Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is more than just a memorial of a historical event; it represents a past event that is made present in our time. Christ’s Eucharistic sacrifice serves as a reminder of the redemptive actions He accomplished for humanity and continues to realize through His one eternal sacrifice. Unlike the crucifixion, which remains a historical event, Christ’s self-offering on the Cross is perpetually present in the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist. This understanding emphasizes that the significance of Christ’s sacrifice is ongoing, bridging the past with the present in the lives of the faithful.

In Leviticus 24:7, it is written: “By each stack put some pure incense as a memorial portion to represent the bread and to be a food offering presented to the LORD.” The term “memorial” in this context is derived from the Hebrew word azkarah (אַזְכָּרָה), which denotes the concept of “making present.” Throughout the Old Testament, there are numerous instances where azkarah refers to sacrifices that are currently being offered, indicating their ongoing presence in time (see Lev 2:2, 9; 6:5; 16:5-12; Num 5:26; 10:10). This suggests that these sacrifices are understood as being offered in memory in the present moment (Ibid., The Biblical Basis for the Eucharist).

In relation to the New Testament, Jesus commands the offering of bread and wine, believed to be transubstantiated into His body and blood, as a memorial offering. This act signifies that His sacrificial offering is made present in time, serving as a reminder of His redemptive work through His singular sacrifice. Consequently, the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass is seen as a re-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, a practice that originates from the Last Supper.

In the Eucharistic celebration, participants join in an expression of unity with the heavenly liturgy, looking forward to the promise of eternal life. The Lord’s Supper serves as a foreshadowing of the wedding feast of the Lamb of God, as described in the heavenly Jerusalem (1 Cor 11:20; Rev 19:9). The Church represents the New Jerusalem that has descended from heaven, replacing the old Jerusalem. This transformation reflects a shift from the Levitical sacrifices that were once offered in the Holy Temple, which was ultimately destroyed by the Romans in A.D. 70, along with the discontinuation of the priestly sacrifices that had been practiced since that time.

Dr. Scott Hahn (Consuming the Word: The New Testament and the Eucharist in the Early Church: Image, 2013), referencing the Book of Revelation chapters 4 and 5, explains that the Apostle John was taken up to heaven on the ‘Lord’s day’ (Sunday) and witnessed a divine liturgy that reflects the celebration of the Mass, known as the marriage feast of the Lamb. In his vision, John sees Christ depicted as our High Priest in the order of Melchizedek, adorned in a liturgical garment similar to that worn by the presiding priest during Holy Mass. The heavenly worship includes an antiphonal chant that parallels the Entrance Antiphon of the Mass.

Central to this vision is an altar where the slain Lamb of God, symbolizing the Holy Eucharist, resides. John also observes golden lampstands (menorahs), reminiscent of those placed on the altar during High Mass, as well as Eucharistic and Baptismal candles. The use of incense to bless the altar is depicted, mirroring the practice in Holy Mass. Furthermore, elements such as the sign of the cross, the greeting, the Rite of Blessing, and the Penitential Rite are recorded in this vision, along with the Gloria and Opening Prayer. These components closely resemble the introductory rites of the Mass, providing a connection between the heavenly liturgy and our earthly celebrations.

The Liturgy of the Word during Holy Mass has connections to John’s vision of the Book or Scroll, which includes messages from Christ. This section encompasses the Alleluia and Gospel readings, alongside the intercessions of angels and saints that parallel the prayers offered by the priest and congregation after the readings. Following this, the celebration transitions to the Liturgy of the Eucharist. In John’s vision, the bowls and chalices he observes symbolize the Preparation of the Gifts, which includes chalices filled with wine and bowls of bread. This vision reflects the Eucharistic introductory command to “lift up our hearts to the Lord,” which is echoed in the dialogue that occurs during the Mass.

The lyrics of “Holy, Holy, Holy” reverberate through the heavenly congregation as worshippers take a kneeling position in reverence. The Great Amen spoken in the sanctuary, along with the image of the sacrificed Lamb, symbolizes the affirmation of faith and the Communion rite in Catholic practice. In the biblical vision of John, he depicts the marriage supper of the Lamb, a sacred event celebrated on earth by the priest when he proclaims, “This is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world. Happy are we who are called to his table,” while raising the Host. John’s vision culminates with a Final Blessing, which reflects the concluding rites and final blessing that typically mark the end of the Holy Mass.

Early Sacred Tradition

St. Ignatius of Antioch (c A.D. 110)

Epistle to Smyrnaeans, 7,1

“They abstain from participating in the Eucharist and from prayer because they do not acknowledge

the Eucharist as the flesh of Jesus Christ, who suffered for our sins and was raised by the Father. Those

who speak against this gift of God bring judgment upon themselves. It would be better for them to revere

it so they might have eternal life. Therefore, it is appropriate to keep away from such people and not talk about them, but instead, pay attention to the teachings of the prophets and, most importantly, the Gospel, which reveals the Passion and fully proves the Resurrection. Avoid all divisions, as they lead to evil.”

St. Justin Martyr (A.D. 155)

First Apology, 66

“For not as common bread and common drink do we receive these; but in like manner as

Jesus Christ, our Saviour, having been made flesh and blood for our salvation, so likewise

have we been taught that the food which is blessed by the prayer of His word and from

which our blood and flesh by transmutation are nourished, is the flesh and blood of that

Jesus who was made flesh.”

St. Irenaeus of Lyons (c A.D. 190)

Against Heresies, V:2,2

“He acknowledged the cup (which is a part of the creation) as his own blood, from which he

bedews our blood; and the bread (also a part of creation) he affirmed to be his own body, from

which he gives increase to our bodies.”

St. Clement of Alexandria (A.D. 202)

The Instructor, 2

“The blood of the grape, symbolizing the Word, wanted to be mixed with water, just as His blood

is mixed with salvation. The blood of the Lord has two aspects: His flesh’s blood, which redeems

us from corruption, and the spiritual blood, which anoints us. Drinking the blood of Jesus means

sharing in the Lord’s immortality, as the Spirit is the driving force of the Word, just as blood is for

the flesh. Therefore, as wine is mixed with water, so is the Spirit with humans. The mixture of

wine and water nourishes faith, while the Spirit leads to immortality. The combination of both

the water and the Word – is called the Eucharist, a renowned and glorious grace. Those who

partake of it by faith are sanctified in body and soul.”

St. Cyprian of Carthage (A.D. 253)

To Caeilius, Epistle 62(63):13

“For because Christ bore us all, in that He also bore our sins, we see that in the water is

understood the people, but in the wine is showed the blood of Christ. Thus, in consecrating the

cup of the Lord, water alone cannot be offered, even as wine alone cannot be offered. For if

anyone offers wine only, the blood of Christ is dissociated from us; but if the water is alone, the

people are dissociated from Christ. When both are mingled and joined with one another by a close

union, there is a completed spiritual and heavenly sacrament. Thus, the cup of the Lord is neither

water nor wine alone unless each is mingled with the other. On the other hand, the body of the

Lord cannot be flour alone or water alone unless both should be united, joined together, and

compacted in the mass of one bread. In this very sacrament, our people are shown to be made

one, so that in like manner as many grains, collected, and ground, and mixed together into one

mass, make one bread; in Christ, who is the heavenly bread, we may know that there is one body,

with which our number is joined and united.”

St. Cyril of Jerusalem (c A.D. 350)

Catechetical Lectures, XXII:8

“Having learned these things, and been fully assured that the seeming bread is not

bread, though sensible to taste, but the Body of Christ; and that the seeming

wine is not wine, though the taste will have it so, but the Blood of Christ; and

that of this David sung of old, saying, And bread strengthens man’s heart, to

make his face to shine with oil, ‘strengthen thou thine heart,’ by partaking

thereof as spiritual, and ‘make the face of thy soul to shine.’”

St. John Chrysostom (A.D. 370)

Gospel of Matthew, Homily 82

“Let us then in everything believe God, and gainsay Him in nothing, though

what is said seem to be contrary to our thoughts and senses, but let His word be

of higher authority than both reasonings and sight. Thus let us do in the

mysteries also, not looking at the things set before us, but keeping in mind His

sayings. For His word cannot deceive, but our senses are easily beguiled. That

hath never failed, but this in most things goeth wrong. Since then the word

saith, ‘This is my body,’ let us both be persuaded and believe, and look at it with

the eyes of the mind. For Christ hath given nothing sensible, but though in

things sensible yet all to be perceived by the mind…How many now say, I

would wish to see His form, the mark, His clothes, His shoes. Lo! Thou seest

Him, Thou touchest Him, thou eatest Him. And thou indeed desirest to see His

clothes, but He giveth Himself to thee not to see only, but also to touch and eat

and receive within thee.”

St. Athanasius of Alexandria (A.D. 373)

Sermon to the Newly Baptized, PG 26, 1325

“You will see the Levites bringing the loaves and a cup of wine, and placing them o

the table. So long as the prayers and invocations have not yet been made, it is mer

bread and a mere cup. But when the great and wonderous prayers have been recited

then the bread becomes the body and the cup the blood of our Lord Jesu

Christ…When the great prayers and holy supplications are sent up, the Word

descends on the bread and the cup, becoming His body.”

St. Ambrose of Milan (A.D. 390-391)

On the Mysteries, 9:50

“Perhaps you will say, ‘I see something else, how is it that you assert that I

receive the Body of Christ?’ And this is the point that remains for us to prove.

And what evidence shall we make use of? Let us prove that this is not what

nature made, but what the blessing consecrated, and the power of blessing is

greater than that of nature, because by blessing nature itself is changed…The

Lord Jesus Himself proclaims: ‘This is My Body.’ Before the blessing of the

heavenly words another nature is spoken of, after the consecration, the Body is

signified. He Himself speaks of His Blood. Before the consecration, it has another

name, after it is called Blood. And you say, Amen, that is, It is true. Let the

heart within confess what the mouth utters, let the soul feel what the voice

speaks.”

He that eats my flesh, and drinks my blood,

dwells in me, and I in him.

John 6, 56

PAX VOBISCUM

Leave a comment